One of the things that really startled me when I began looking into home schooling was that fine art and classical music should be introduced at a young age. For me, art and music consisted of giving my kids a bag of crayons, a stack of coloring books, and popping in a Veggie Tales or Wiggles CD . . . while I, in turn, popped in a pair of ear plugs to avoid insanity.

When I read the chapters on art and music in The Well-Trained Mind, I didn’t know whether I should do the dance of joy or rip the pages from the book and expunge their contents from my mind. On the one hand, the Wise ladies have a point: if you want your kids to appreciate good art and good music, you have to expose them to good art and good music. But to have them sit there and look at a Raphael for ten minutes, or to have them listen to Bach for fifteen? Come on. High culture for my kids has been Stan Lee and Johnny Cash.

Thankfully, Jem was only in kindergarten, and that gave me a year to think about how I wanted to teach art and music. Thanks to Charlotte Mason’s A Philosophy of Education and Elizabeth Foss’s Real Learning, I think I’ve developed a plan . . . at least for this next year. It consists in making fine art and classical music part of their lives.

I don’t particularly care if my first-grader can distinguish a Cezanne from a Van Gogh (though that would be nice) or Bach from Wagner (thought that would be nice, too). More to the point, I don’t want them to think of fine art and classical music as something to be studied; rather, I want it to be part of their life, something they live.

Regarding music -- I decided to forgo “formal” music appreciation and instead play music during meals, in the car, and throughout the day. Also, I decided not to make a big deal about what we were listening to. For example, we might listen to Bach during breakfast, Credence Clearwater Revival over lunch, and Miles Davis at dinner. Good music is good music, whether or not it’s classical, country-rock, or blues. Besides, at some point in time, my kids are going to choose what kind of music they want to listen to, and they'll probably choose some form of popular music; my hope is that by exposing them to Johnny Cash, CCR, The Beatles, Tom Petty, etc., they’ll naturally avoid the schlock that passes itself off as music nowadays. Now if that’s not idealist, tell me what is?

Art is a little bit different. How exactly does one fit art into one's everyday experience. Following The Well-Trained Mind, I decided to join art with my kids study of history. Since we’ll be studying the ancient world this next year, that’s the kind of art we’ll be looking at.

And that’s all we’ll be doing -- looking at it. I have a big, thick, coffee-table book of ancient Egypt, and my plan is to sit down once or twice a week with Jem and let him page through it for fifteen minutes or so. We can talk about it if he wants, but silence is fine, too. Basically my goal, which I learned from Charlotte Mason (though I can’t find the passage at the moment), is to fill my kids head with images of the ancient world so that the ancient world is a real and vivid place for them. And if Jem wants to look at the book on his own, without any guidance from me, then more power to him. In fact, I'm going to encourage him to do so.

That’s basically it for art and music appreciation. It’s pretty simple, and very much part of our everyday life. My goal is simple: good art and good music are not things set apart, things that only stodgy folks like Frasier and Niles Crane enjoy; rather, they are things anyone can enjoy -- indeed, things that enrich our lives.

As far as the practice of art and music goes, that's a bit easier. With art, we'll be using Drawing with Children. I used this a bit last year, but it seemed too advanced for Jem. However, since then, he's attended an art class at a local Michael's (which he loved) and he's asked me several times over the past few weeks when we're going to use "that book that teaches you how to draw lions." So my plan is simple: a "formal" art lesson every two weeks during which I sit down and review the basic strokes with Jem and maybe even give him an assignment.

Anything beyond that would be too much. Jem loves to draw and cut and paint and "do projects," as he says. So a formal lesson every couple of weeks from Drawing with Children joined to the monthly art class at the local Michael's, along with his own proclivity to art, should be enough for him to make solid progress.

I have a fairly strong background in music; I studied classical guitar throughout junior high and high school. When Jem turned seven in December, I'm going to start teaching him the piano. I'm self-taught on the piano, and I know enough about music theory and sound musicianship to lay the foundations. If he really takes to it, then I'll find him a teacher. If not, I'll make him study for two year then drop it.

Monday, August 22, 2016

Friday, August 19, 2016

Curriculum: History

Once again, my history program is inspired by the one outline in The Well-Trained Mind. In case you’re not aware of it, The Well-Trained Mind claims that history ought to be studied chronologically over a four-year period. The outline looks something like this:

Year 1 -- The Ancient World (5000 BC - 500 AD)

Year 2 -- The Medieval World (500 - 1500)

Year 3 -- The Modern World (1500-1800)

Year 4 -- The Contemporary World (1800-2000)

Though I’m going to hold to this plan, I no longer think it’s imperative to teach history in this way. In fact, I think outside of the basic skills necessary to reading, writing, math, and Latin, almost all systematic study of any subject falls on deaf ears until kids are in high school -- possibly even at late as college. I don’t think kids have the analytical powers necessary for systematic study, and when that skill finally does come, if they have a mind full of good and useful facts and ideas, they’ll naturally connect the dots.

The reason I like this plan is because it works for me. It makes my life easier. I know what we’ll be doing over the next four years. Furthermore, the plan is easily adaptable.

Also, I don’t think grade-school kids can study history as history. That's something I learned from Andrew Campbell’s The Latin-Centered Curriculum. So my history study is going to focus more on mythology, legends, and biographies. My goal is twofold: to make them culturally literate, and to prepare them for a more detailed study of history when they get older.

Let me see if I can explain myself a little better. A child can’t learn algebra unless he’s already mastered the basics of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division; and those skills presuppose a more basic set of skills. Likewise, a child can’t study history as history until he’s learned a more basic set of information: names of people and basic geography, primarily. So my goal during the first four years of history is little more than reading biographies, legends, mythology, and learning geography. In other words, giving my kids what the desperately want at this age -- fact . . . facts that will be essential to the real study of history.

What I also learned from The Latin-Centered Curriculum is that sometimes it’s better to go slower and more deeply than to go quickly and only skim the surface. So even though I’m following The Well-Trained Mind’s history program, I’ve modified it.

This year -- which will be Year 1 -- instead of focusing on the whole of the ancient world, we’re just going to focus on the four great cultures that shaped Western Civilization: Egypt, Israel, Greece, and Rome. I’ve divided the year into four quarters, and each quarter will bring with it a new culture.

I’m using A Child’s History of the World as my basic spine, as well as Susan Wise Bauer’s The Story of the World: Activity Book One for projects and maps. I'll also be supplementing these basic texts with many books of legends, mythologies, and biographies that I’ll be reading aloud to my kids.

I plan to do history twice a week. Day 1 (Monday) will be focused on the chapter form The Story of the World, a project or map work. The day will conclude with Jem doing a narration of what he’s learned, which I’ll type up and put in a folder.

Day 2 (Wednesday) will begin with a quick review of what we studied on Day 1, then 30 minutes of so of me reading aloud, either a biography or a book of mythology. That’s it. I’m not going to ask any questions, or have Jem do anything extra . . . unless he volunteers.

All in all, I'm anticipating no more than 90 minutes a week.

Oh, yeah, I also made my own Staircase of Time -- the one at the beginning of A Child’s History of the World -- which we’ll be filling out over the next few years. Just as a map should give Jem a sense of place, my hope is that the Staircase of Time will give him a sense of time.

If I get around to it, I’ll take a photo of it and post it -- probably sometime next week.

Year 1 -- The Ancient World (5000 BC - 500 AD)

Year 2 -- The Medieval World (500 - 1500)

Year 3 -- The Modern World (1500-1800)

Year 4 -- The Contemporary World (1800-2000)

Though I’m going to hold to this plan, I no longer think it’s imperative to teach history in this way. In fact, I think outside of the basic skills necessary to reading, writing, math, and Latin, almost all systematic study of any subject falls on deaf ears until kids are in high school -- possibly even at late as college. I don’t think kids have the analytical powers necessary for systematic study, and when that skill finally does come, if they have a mind full of good and useful facts and ideas, they’ll naturally connect the dots.

The reason I like this plan is because it works for me. It makes my life easier. I know what we’ll be doing over the next four years. Furthermore, the plan is easily adaptable.

Also, I don’t think grade-school kids can study history as history. That's something I learned from Andrew Campbell’s The Latin-Centered Curriculum. So my history study is going to focus more on mythology, legends, and biographies. My goal is twofold: to make them culturally literate, and to prepare them for a more detailed study of history when they get older.

Let me see if I can explain myself a little better. A child can’t learn algebra unless he’s already mastered the basics of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division; and those skills presuppose a more basic set of skills. Likewise, a child can’t study history as history until he’s learned a more basic set of information: names of people and basic geography, primarily. So my goal during the first four years of history is little more than reading biographies, legends, mythology, and learning geography. In other words, giving my kids what the desperately want at this age -- fact . . . facts that will be essential to the real study of history.

What I also learned from The Latin-Centered Curriculum is that sometimes it’s better to go slower and more deeply than to go quickly and only skim the surface. So even though I’m following The Well-Trained Mind’s history program, I’ve modified it.

This year -- which will be Year 1 -- instead of focusing on the whole of the ancient world, we’re just going to focus on the four great cultures that shaped Western Civilization: Egypt, Israel, Greece, and Rome. I’ve divided the year into four quarters, and each quarter will bring with it a new culture.

I’m using A Child’s History of the World as my basic spine, as well as Susan Wise Bauer’s The Story of the World: Activity Book One for projects and maps. I'll also be supplementing these basic texts with many books of legends, mythologies, and biographies that I’ll be reading aloud to my kids.

I plan to do history twice a week. Day 1 (Monday) will be focused on the chapter form The Story of the World, a project or map work. The day will conclude with Jem doing a narration of what he’s learned, which I’ll type up and put in a folder.

Day 2 (Wednesday) will begin with a quick review of what we studied on Day 1, then 30 minutes of so of me reading aloud, either a biography or a book of mythology. That’s it. I’m not going to ask any questions, or have Jem do anything extra . . . unless he volunteers.

All in all, I'm anticipating no more than 90 minutes a week.

Oh, yeah, I also made my own Staircase of Time -- the one at the beginning of A Child’s History of the World -- which we’ll be filling out over the next few years. Just as a map should give Jem a sense of place, my hope is that the Staircase of Time will give him a sense of time.

If I get around to it, I’ll take a photo of it and post it -- probably sometime next week.

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

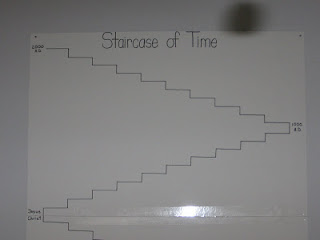

Staircase of Time

The Well-Trained Mind recommends that middle-grade students (that is, grades 5-8) should make a timeline each year in order to understand both the scope of history as well as the chronological relationship between historical figures and events.

Unfortunately for us eager parents who see homeschooling as a means to self-education, younger children can't comprehend the timeline. It's too abstract. Thus, it was a great surprise and delight to discover that there is an alternative to the timeline, one that's easier for younger children to understand -- it's called the Staircase of Time. You can find it at the beginning of V. M. Hillyer's A Child's History of the World.

I was going to buy one for Jem to use during his first trip through history. However, much to my annoyance, I discovered the one you can buy from the Calvert School is already filled out for the kids. That's not only not any fun, it doesn't help kids learn the basic facts of history. The kids don't get to decide what to write down, and too much much information is coming to them at once. Better to start with a blank Staircase and fill it in as you go. That way, the shape of history begins to take form in the child's mind. So I decided to make my own. It looks like this:

I was going to use ordinary poster board, but my wife encouraged me to use the thicker version (I can't recall the name off hand) because of its durability. We'll be using this over the next two years at least.

When I explained the Staircase to Jem, he immediately understood the concept. I pointed to the top and said, "This is where we are."

Then I pointed to the middle and told him this was the period we were going to be learning about next year, in the 1st grade.

Then I pointed to the bottom and explained that what happened down here is so old that we hardly know anything about it.

Each step equals 100 years. This will work fine until we start American history in two years, when Jem is in the 3rd grade. Thus, I plan to make a new one for American history. It will begin with the year 1400, and each step will equal 10 years.

Unfortunately for us eager parents who see homeschooling as a means to self-education, younger children can't comprehend the timeline. It's too abstract. Thus, it was a great surprise and delight to discover that there is an alternative to the timeline, one that's easier for younger children to understand -- it's called the Staircase of Time. You can find it at the beginning of V. M. Hillyer's A Child's History of the World.

I was going to buy one for Jem to use during his first trip through history. However, much to my annoyance, I discovered the one you can buy from the Calvert School is already filled out for the kids. That's not only not any fun, it doesn't help kids learn the basic facts of history. The kids don't get to decide what to write down, and too much much information is coming to them at once. Better to start with a blank Staircase and fill it in as you go. That way, the shape of history begins to take form in the child's mind. So I decided to make my own. It looks like this:

I was going to use ordinary poster board, but my wife encouraged me to use the thicker version (I can't recall the name off hand) because of its durability. We'll be using this over the next two years at least.

When I explained the Staircase to Jem, he immediately understood the concept. I pointed to the top and said, "This is where we are."

Then I pointed to the middle and told him this was the period we were going to be learning about next year, in the 1st grade.

Then I pointed to the bottom and explained that what happened down here is so old that we hardly know anything about it.

Each step equals 100 years. This will work fine until we start American history in two years, when Jem is in the 3rd grade. Thus, I plan to make a new one for American history. It will begin with the year 1400, and each step will equal 10 years.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)